A Review of Evidence-based Psychosocial Interventions for Bipolar Dis- Order

- Review

- Open Admission

- Published:

Psychosocial treatment and interventions for bipolar disorder: a systematic review

Annals of Full general Psychiatry volume xiv, Commodity number:19 (2015) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic disorder with a high relapse rate, significant general disability and burden and with a psychosocial harm that often persists despite pharmacotherapy. This indicates the need for effective and affordable adjunctive psychosocial interventions, tailored to the individual patient. Several psychotherapeutic techniques accept tried to fill up this gap, just which intervention is suitable for each patient remains unknown and it depends on the phase of the disease.

Methods

The papers were located with searches in PubMed/MEDLINE through May 1st 2015 with a combination of key words. The review followed the recommendations of the Preferred Items for Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.

Results

The search returned 7,332 papers; after the deletion of duplicates, 6,124 remained and eventually 78 were included for the analysis. The literature supports the usefulness only of psychoeducation for the relapse prevention of mood episodes and only in a selected subgroup of patients at an early phase of the disease who have very good, if non complete remission, of the acute episode. Cognitive-behavioural therapy and interpersonal and social rhythms therapy could have some beneficial effect during the astute phase, merely more data are needed. Mindfulness interventions could only decrease feet, while interventions to improve neurocognition seem to exist rather ineffective. Family intervention seems to accept benefits mainly for caregivers, but it is uncertain whether they have an event on patient outcomes.

Decision

The electric current review suggests that the literature supports the usefulness but of specific psychosocial interventions targeting specific aspects of BD in selected subgroups of patients.

Background

Our contemporary agreement of bipolar disorder (BD) suggests that there is an unfavorable outcome in a significant proportion of patients [1, 2]. In spite of recent advances in pharmacological treatment, many BD patients will eventually develop chronicity with meaning general inability and burden. The burden will be pregnant also for their families and the lodge as a whole [three, iv]. Today, nosotros also know that unfortunately, symptomatic remission is not identical and does not imply functional recovery [5–7].

Since pharmacological treatment often fails to address all the patients' needs, in that location is a growing need for the development and implementation of constructive and affordable interventions, tailored to the individual patient [8]. The early successful treatment, with full recovery if possible, as well as the direction of subsyndromal symptoms and of psychosocial stress and poor adherence are factors predicting before relapse and poor overall outcome [ix, 10].

In this frame, there are several specific adjunctive psychotherapies which accept been adult with the aim of filling the to a higher place gaps and eventually ameliorate the affliction outcome [11], just it is still unclear whether they truly work and which patients are eligible and when [12–19].

The current report is a systematic review of the efficacy of available psychosocial interventions for the treatment of adult patients with BD.

Methods

Reports investigating psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions in BD patient samples were located with searches in Pubmed/MEDLINE through May one, 2015. Just reports in English were included.

The Pubmed database was searched using the search terms 'bipolar' and 'psychotherapy' or 'cognitive-behavioral' or 'CBT' or 'psychoeducation' or 'interpersonal and social rhythm therapy' or 'IPSRT' or 'family unit intervention' or 'family therapy' or 'group therapy' or 'intensive psychosocial intervention' or 'cognitive remediation' or 'functional remediation' or 'Mindfulness'.

The following rules were applied for the choice of papers:

- 1.

Papers in English language language.

- 2.

Randomized controlled trials.

This review followed the recommendations of the Preferred Items for Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) argument [20].

Results

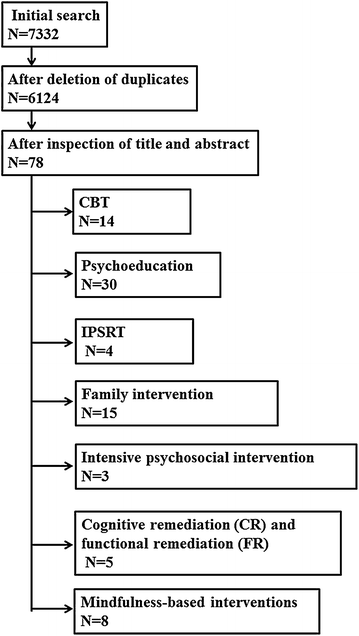

The search returned 7,332 papers, and after the deletion of duplicates 6,124 remained for farther assessment. Afterward assessing these papers on the basis of title and abstract, the remaining papers were (Effigy 1). The number of newspaper reported for each intervention includes RCTs, mail hoc analyses and meta-analyses together.

The PRISMA flowchart.

Cerebral-behavioural therapy (CBT)

The efficacy of CBT in BD was investigated in 14 studies which utilized CBT equally adjunct handling to pharmacotherapy or handling as usual (TAU). They utilized some kind of control intervention which should non be considered equally an adequate placebo. It is also interesting that the oldest study was conducted in 2003.

This first study lasted 12 months and concerned 103 BD-I patients during the astute depressive phase and randomized them to 14 sessions of CBT or a control intervention. There was not any placebo condition. These authors reported that at finish point fewer patients in the CBT grouping relapsed in comparison to controls (44 vs. 75%; HR = 0.twoscore, P = 0.004), had shorter episode elapsing, less admissions and mood symptoms, and higher social performance [21]. It was disappointing that the extension of this study (eighteen months follow-up) was negative concerning the relapse rate [22].

A second trial included 52 BD patients and was also negative apropos the long-term efficacy after comparing CBT plus additional emotive techniques vs. TAU [23]. On the other hand, the comparison of CBT plus psychoeducation vs. TAU in twoscore BD patients reported a beneficial result even after 5 years in terms of symptoms and social–occupational functioning. Nevertheless, that written report did non study the rate of recurrences and the time to recurrence [24]. A study in 79 BD patients (52 BD-I and 27 BD-II) compared CBT plus psychoeducation vs. psychoeducation alone and reported that the combined handling group had 50% fewer depressed days per month, while at the aforementioned time the psychoeducation alone grouping had more than antidepressant use [25]. Another study on 41 BD patients randomized to CBT vs. TAU reported similar results and an improvement in symptoms, frequency and duration of episodes [26].

An xviii-month written report compared CBT vs. TAU in 253 BD patients and reported that at end point, in that location were no differences between groups with more than than one-half of the patients having a recurrence. Information technology is interesting that a post hoc analysis suggested that CBT was significantly more than effective than TAU in those patients with fewer than 12 previous episodes, but less effective in those with more than episodes [13]. Like negative results were reported concerning the number of episodes and time to relapse by some other 12-month study of CBT vs. TAU in 50 BD patients in remission [17]. Again, negative findings concerning the relapse charge per unit were reported past a 2-year study on 76 BD patients randomized to receive 20 sessions of CBT vs. back up therapy [15]. Finally, the apply of combined CBT and pharmacotherapy in 40 patients with refractory bipolar disorder suggested that the combination group had less hospitalization events in comparison to the group in the 12-month evaluation (P = 0.015) and lower depression and feet in the 6-month (P = 0.006; P = 0.019), 12-month (P = 0.001; P < 0.001) and 5-twelvemonth (P < 0.001, P < 0.001) evaluation fourth dimension points. However it is interesting that subsequently the five-yr follow-up, 88.nine% of patients in the control group and 20% of patients in the combination group showed persistent affective symptoms and difficulties in social–occupational functioning [27].

The use of CBT in BD comorbid with social feet disorder is of hundred-to-one efficacy [28], while there are some preliminary data on the efficacy of an Internet-based CBT intervention [29] also as recovery-focused add-on CBT [30] and CBT for insomnia [31] in comparison to TAU.

The review of the available information and then far give express support for the usefulness of CBT during the astute phase of bipolar low as adjunctive handling in patients with BD, simply definitely not for the maintenance phase. During the maintenance stage, booster sessions might be necessary, only the data are mostly overall negative. Probably, patients at earlier stages of the illness might benefit more from CBT. Unfortunately the blazon of patients who are more likely to benefit from CBT constitutes a minority in usual clinical practice.

Psychoeducation

The basic concept behind psychoeducation for BD concerns the training of patients regarding the overall awareness of the disorder, treatment adherence, avoiding of substance abuse and early on detection of new episodes. The efficacy of psychoeducation in BD was investigated in 30 studies, all of which utilized psychoeducation as offshoot treatment to pharmacotherapy or TAU. All these studies utilize some kind of control intervention which should not be considered as an adequate placebo. It is likewise interesting that the oldest written report was conducted in 1991.

The earliest psychoeducational study was open and uncontrolled and reported that giving information nearly lithium improved the overall mental attitude towards treatment [32, 33]. A similar small study was conducted a few years later on and reported similar results [34]. However, the get-go written report on the wide teaching of patients to recognize and identify the components of their disease with emphasis on early symptoms of relapse and recurrence and to seek professional aid as early on equally possible had not been conducted until 1999. It included 69 patients for 18 months and compared psychoeducation (limited number of sessions; 7–12) vs. TAU. It reported a meaning prolongation of the time to first manic relapse (P = 0.008) and significant reductions in the number of manic relapses over xviii months (30 vs. 52%; P = 0.013) every bit well as improved overall social functioning. Psychoeducation had no effect on depressive relapses [35].

In a more systematic way, the efficacy of the adjunctive grouping psychoeducation was tested by the Barcelona grouping. Their trial included 120 euthymic BD patients who were randomly assigned to 21 sessions of grouping psychoeducation vs. non-specific group meetings. The study included a follow-upwards with a duration of two and 5 years. The results suggested that psychoeducation exerted a benign effect on the charge per unit of and the time to recurrence equally well as concerning hospitalizations per patient. At the end of the 2-year follow-upward, 23 subjects (92%) in the control group fulfilled the criteria for recurrence versus xv patients (threescore%) in the psychoeducation group (P < 0.01). This benign effect was high and was not reduced after 5 years (any episode 0.79 vs. 0.87; mania 0.40 vs. 0.57; hypomania 0.27 vs. 0.42 and mixed episodes 0.34 vs. 0.61), except for depressive episodes (0.91 vs. 0.80) [36–38].

The literature suggests that psychoeducation should be wide and that enhanced relapse prevention solitary does non seem to work. This was the conclusion from another study with a dissimilar design. That study reported that simply occupational performance, merely non time to recurrence, improved with an intervention consisting of training community mental health teams to deliver enhanced relapse prevention [39]. Additionally, a study with a 12-month follow-up and with a similar design to the first study of the Barcelona grouping, merely with 16 sessions, reported no differences between groups in mood symptoms, psychosocial operation and quality of life. It did notice, however, that there was a difference in the subjectively perceived overall clinical improvement past subjects who received psychoeducation. The authors suggested that characteristics of the sample could explain this discrepancy, every bit patients with a more than advanced stage of disease might have a worse response to psychoeducation [16]. In accordance with the in a higher place, a mail service hoc analysis of the original Barcelona data revealed that patients with more than 7 episodes did not prove significant improvement with group psychoeducation in time to recurrence, and those with more than than 14 episodes did not benefit from the treatment in terms of fourth dimension spent ill [40]. A 2-year follow-upwards in 108 BD patients investigated psychoeducation plus pharmacotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy alone. Psychoeducation concerned eight, 50-min sessions of psychological education, followed past monthly telephone follow-upward care and psychological back up. The results suggested that psychoeducation improved medication compliance (P = 0.008) and quality of life (P < 0.001) and had fewer hospitalizations (P < 0.001) [41]. Some other written report randomized 80 BD patients to either the psychoeducation or the control grouping and reported that the psychoeducation grouping scored significantly college on performance levels (emotional performance, intellectual functioning, feelings of stigmatization, social withdrawal, household relations, relations with friends, participating in social activities, daily activities and recreational activities, taking initiative and self-sufficiency, and occupation) (P < 0.05) compared with the control group subsequently psychoeducation [42].

A prospective v-year follow-upwards of 120 BD patients suggested that group psychoeducation might be more price-effective [43]. In support of the cost-effectiveness of psychoeducation was one trial in 204 BD patients which compared xx sessions of CBT vs. 6 sessions of group psychoeducation and reported that overall the outcome was similar in the two groups in terms of reduction of symptoms and likelihood of relapse, simply psychoeducation was associated with a decrease of costs ($180 per bailiwick vs. $1,200 per subject for CBT) [44] Currently, there are some proposals of online psychoeducation programmes, but results are still inconclusive or pending [45, 46].

More complex multimodal approaches and multicomponent care packages have been developed and usually psychoeducation is a core element. One of these packages as well included CBT and elements of dialectical behaviour therapy and social rhythms and has shown a beneficial effect after the one-twelvemonth follow-up in comparison to TAU [47]. Another included a combination of CBT plus psychoeducation and reported that it was more effective in comparing to TAU in 40 refractory BD patients concerning hospitalization and balance symptoms at 12 months follow-up [27]. A collaborative intendance written report on 138 patients and follow-up of 12 months as well gave positive results [48]. One multicentred Italian study assessed the efficacy of the Falloon model of psychoeducational family intervention (PFI), originally adult for schizophrenia management and adapted to BD-I disorder. It included 137 recruited families, of which seventy were allocated to the experimental group and 67 to the TAU group. At the cease of the intervention, pregnant improvements in patients' social performance and relatives' burden were found in the treated grouping compared to TAU [49]. In general, the beneficial effect seems to be present apropos manic but not depressive episodes [50, 51], while a benefit on social role function and quality of life seems also to exist present [50].

The comparison of 12 sessions of psychoeducation vs. TAU in 71 BD patients reported that at 6 weeks, the intervention improved handling adherence [52], while another on 61 BD-Ii patients reported no significant event on the regulation of biological rhythms when compared to standard pharmacological treatment [53]. No significant effect was reported concerning the quality of life past another recent study on 61 immature bipolar adults [54]. On the reverse, a trial on 47 BD patients reported that a psychoeducation programme designed for internalized stigmatization may have positive furnishings on the internalized stigmatization levels of patients with bipolar disorder [55].

There is preliminary evidence that a Spider web-based handling arroyo in BD ('Living with Bipolar'—LWB intervention) is feasible and potentially effective [56]; even so, other Web-based attempts returned negative results [57]. Automatic mobile-telephone intervention is another option and it has been reported to be feasible, acceptable and might enhance the impact of brief psychoeducation on depressive symptoms in BD. However, sustainment of gains from symptom self-management mobile interventions, one time stopped, may be limited [58].

Ane meta-analysis of 16 studies, 8 of which provided data on relapse reported that psychoeducation appeared to be effective in preventing any relapse (OR: i.98–ii.75; NNT: 5–7) and manic/hypomanic relapse (OR: one.68–2.52; NNT: 6–viii), but not depressive relapse. That meta-analysis reported that group, but non individually, delivered interventions were effective against both poles of relapse [59].

In summary, the literature suggests that interventions of 6-month group psychoeducation seem to exert a long-lasting rubber effect. However this is rather restricted to manic episodes and to patients at the before stages of the disease who have achieved remission earlier the intervention has started. Although the mechanism of activity of psychoeducation remains unknown, it is highly likely that the beneficial outcome is mediated past the enhancement of treatment adherence, the promoting of lifestyle regularity and good for you habits and the instruction of early on detection of prodromal signs.

Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT)

Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy is based on the hypothesis that in vulnerable individuals, the experience of stressful life events and unstable or disrupted daily routines can lead to affective episodes via cyclic rhythm instability [18]. In this frame, IPSRT includes the management of affective symptoms through comeback of adherence to medication and stabilizing social rhythms and the resolution of interpersonal issues. Four papers investigating its efficacy were identified.

The kickoff report apropos its efficacy in BD included 175 acutely ill BD patients and followed them for two years. It included four treatment groups, reflecting IPSRT vs. intensive clinical management during the acute and the maintenance stage. The results revealed no difference between interventions in terms of time to remission and in the proportion of patients achieving remission (lxx vs. 72%), although those patients who received IPSRT during the acute treatment phase survived longer without an episode and showed higher regularity of social rhythms [60]. In spite of some encouraging findings from mail hoc analysis, there were somewhen no significant differences between genders and apropos the comeback in occupational functioning [61]. More recently, a 12-week study in which unmedicated depressed BD-II patients were randomized to IPSRT (Due north = 14) vs. treatment with quetiapine (up to 300 mg/twenty-four hour period; N = 11), showed that both groups experienced significant reduction in symptoms over fourth dimension, but at that place were no group-by-time interactions. Response and drib-out rates were similar [62]. Finally, one 78-week trial investigated the efficacy of IPSRT vs. specialist supportive intendance on depressive and mania outcomes and social functioning, and mania outcomes in 100 young BD patients. The results revealed no meaning deviation between therapies [63].

Overall, there are no disarming data on the usefulness of IPSRT during the maintenance stage of BD. There are, even so, some data suggesting that if applied early and particularly already during the acute phase, information technology might prolong the time to relapse.

Family intervention

The standard family unit intervention for BD targets the whole family and not only the patient and includes elements of psychoeducation, communication enhancement and problem-solving skills training. It too includes support and self-care grooming for caregivers. Xv papers concerning the efficacy of family unit intervention in BD were found.

The first study on this intervention took part in 1991 and reported that carer-focused interventions improve the knowledge of the illness [64]. Since then, there have been a number of studies which in full general support the use of adjunctive family unit-focused treatment. There are different designs and approaches which were tested in essentially open trials.

One intervention design consists of 21 ane-h sessions which combine psychoeducation, communication skills training and problem-solving training. The sessions accept place at habitation and included both the patient and his/her family unit during the mail service-episode period. The treatment has shown its efficacy vs. crunch management in 101 BD patients in reducing relapses (35 vs. 54%) and increasing time to relapse (53 vs. 73 weeks, respectively) [65, 66]. It was too reported to reduce hospitalization risk compared with individual treatment (12 vs. 60%) [67]. It is important that the benefits extended to the 2-year follow-up were particularly useful for depressive symptoms, in families with high expressed emotion and for the improvement of medication adherence [66]. Like results were reported by a study of 81 BD patients and 33 family dyads, which reported that the odds ratio for hospitalization at i-yr follow-up was related with high perceived criticism (by the patients from their relatives), poor adherence and with the relatives' lack of noesis concerning BD (OR: three.3; 95% CI i.3–8.6) [68].

Adjunctive psychoeducational marital intervention in acutely ill patients was reported to have a beneficial effect concerning medication adherence and global functioning, but not for symptoms [69]. Neither adjunctive family therapy nor adjunctive multifamily grouping therapy improves the recovery rate from astute bipolar episodes when compared with pharmacotherapy lone [14]. These interventions could be beneficial for patients from families with high levels of impairment and could consequence in a reduction of both the number of depressive episodes and the time spent in depression (Cohen d = 0.7–1.0) [70]. In this frame, in those patients who recovered from the intake episode, multifamily group therapy was associated with the lowest hospitalization risk [71].

Another format included a 90-min elapsing, delivered to caregivers of euthymic BD patients; after fifteen-months, it was reported to have both reduced the take a chance of recurrence in comparison to a control grouping (42 vs. 66%; NNT: 4.one with 95% CI ii.4–19.ane) and too to have delayed recurrence [72]. It was particularly efficacious in the prevention of hypomanic/manic episodes and also in the reduction of the overall family brunt [73]. Information technology had been shown earlier that carer-focused interventions improve the knowledge of the illness [64], reduce burden [74] and also reduce the general and mental wellness risk of caregivers [75].

Another format of intervention included 12 sessions of grouping psychoeducation for the patients and their families. It has been found superior to TAU in 58 BD patients concerning the prevention of relapses, the decrease of manic symptoms and the improvement of medication adherence [76]. Finally, the comparing of family-based therapy (FBT) vs. brief psychoeducation (crisis management) in 108 patients with BD reported that the issue depended on the existing levels of appropriate self-cede [77].

Overall, the literature supports the decision that interventions which focus on families and caregivers exert a beneficial impact on family members, simply the effect on the patients themselves is controversial. The result includes issues ranging from subjective well-existence to full general health, simply it is near sure that there is a beneficial event on problems like treatment adherence.

Intensive psychosocial intervention

There are iii papers investigating various methods of intensive psychosocial intervention. 'Intensive' psychotherapy has been tested on 293 acutely depressive BD outpatients in a multi-site study. Patients were randomized to 3 sessions of psychoeducation vs. up to 30 sessions of intensive psychotherapy (family-focused therapy, IPSRT or CBT). The results suggested that the intensive psychotherapy grouping showed higher recovery rates, shorter times to recovery and greater likelihood of being clinically well in comparison to patients on short intervention [78]. The functional outcome was also reported to be better afterward 1 twelvemonth [79]. A second trial randomized 138 BD patients to receive collaborative intendance (contracting, psychoeducation, problem-solving treatment, systematic relapse prevention and monitoring of outcomes) vs. TAU. The results suggested that collaborative care had a pregnant and clinically relevant effect on the number of months with depressive symptoms, besides every bit on severity of depressive symptoms, but there was no effect on symptoms of mania or on handling adherence [48].

Cognitive remediation (CR) and functional remediation (FR)

Cognitive remediation and functional remediation tailored to the needs of BD patients include instruction on neurocognitive deficits, advice, autonomy and stress management. There are five papers on the efficacy of CR and FR.

I uncontrolled study in fifteen BD patients applied a blazon of CR and focused on mood monitoring and rest depressive symptoms, organization, planning and time management, attention and memory. The results suggested that at that place was an improvement of residual depressive symptoms, executive functions and general functioning. Patients with greater neurocognitive impairment had less benefit from the intervention [80]. The combination of neurocognitive techniques with psychoeducation and problem solving within an ecological framework was tested in a multicentre trial in 239 euthymic BD patients with a moderate–severe degree of functional harm (N = 77) vs. psychoeducation (N = 82) and vs. TAU (N = lxxx). At end point, the combined programme was superior to TAU, simply not to psychoeducation lonely [81, 82]. Finally, a minor study in 37 BD and schizoaffective patients tested social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) every bit adjunctive to TAU (N = 21) vs. TAU solitary (N = sixteen). At that place was no difference between groups concerning social operation, but there was a superiority of the combination group in the improvement of emotion perception, theory of mind, hostile attribution bias and depressive symptoms [83]. A post hoc analysis using data of 53 BD-II outpatients compared FR vs. psychoeducation and vs. TAU, but the results were negative [84].

Mindfulness-based interventions

Mindfulness-based intervention aims to enhance the ability to keep one'south attending on purpose in the present moment and non-judgmentally. Specifically for BD patients, information technology includes education about the disease and relapse-prevention, combination of cognitive therapy and training in mindfulness meditation to increase the awareness of the patterns of thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations and the development of a dissimilar mode (non-judgementally) of relating to thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations. It also promotes the power of the patients to choose the virtually skilful response to thoughts, feelings or situations. There are 8 studies on the efficacy of mindfulness-based intervention in BD.

The first study concerning the application of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in BD tested information technology vs. waiting list and included only eight patients in each grouping. The results suggested a beneficial effect with a reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms [85]. A second study included 23 BD patients and ten healthy controls and investigated MBCT vs. waiting list and the results were compared with those of 10 healthy controls. The results suggested that post-obit MBCT, there were significant improvements in BD patients concerning mindfulness, anxiety and emotion regulation, working memory, spatial memory and verbal fluency compared to the waiting list grouping [86]. The biggest study so far concerning MBCT included 95 BD patients and tested MBCT as adjunctive to TAU (N = 48) vs. TAU alone (North = 47) and followed the patients for 12 months. The results showed no departure betwixt handling groups in terms of relapse and recurrent rates of any mood episodes. At that place was some benign issue of MBCT on anxiety symptoms [87, 88]. Recently, the focus has expanded to analyze the bear upon of MBCT on brain activity and cognitive performance in BD, just the findings are hard to interpret [86, 89, 90].

A study which practical dialectical behaviour therapy in which mindfulness represented a large component also reported some positive outcomes [91]. 1 study on mindfulness grooming reported negative results in BD patients [92].

In conclusion, the literature does not support a beneficial effect of MBCT on the core bug of BD. In that location are some data suggesting a benign event on feet in BD patients. So far, in that location are no data supporting its efficacy in the prevention of recurrences.

Discussion

The current review suggests that the literature supports the usefulness but of psychoeducation for the relapse prevention of mood episodes and unfortunately only in a selected subgroup of patients at an early stage of the disease who take very good if not complete remission of the acute episode. On the other manus, CBT and IPSRT could have some benign effect during the astute phase, only more data are needed. Mindfulness interventions could merely decrease anxiety, while interventions to amend neurocognition seem to be rather ineffective. Family intervention seems to have benefits mainly for caregivers, but it is uncertain whether they have an effect on patient outcomes. A summary of the specific areas of efficacy for each of the above-mentioned interventions is shown in Table 1.

An boosted important conclusion is that concerning the quality of the data available: the studies on BD patients suffer from the aforementioned limitations and methodological problems as all psychotherapy trials practice. Information technology is well known that this kind of studies suffers from problems pertaining to blindness and the nature of the control intervention. Additionally, the grooming of the therapist and the setting itself might play an of import office. Information technology is quite different to apply the aforementioned intervention in specialized centres than in real-world settings in everyday clinical practice. Even worse, inquiry is not done in a standardized way and the gathering of data is far from systematic. The studies are rarely registered, adverse events are not routinely assessed, outcomes are not hierarchically stated a priori and too many post hoc analyses have been published without being stated as such. In that location is a lack of replication of the aforementioned treatment by different research groups under the same conditions.

In that location are unlike theories on the mechanisms responsible for the efficacy of the psychosocial treatments. 1 suggestion concerns the enhancement of handling adherence [93], while another proposes that improving lifestyle and especially biological rhythms, food intake and social zeitgebers could be the primal factors [sixty]. Also, it has been proposed that the mechanism concerns the changing of dysfunctional attitudes [23], the improvement of family interactions [94] or the enhanced ability for the early identification of signs of relapse [35].

Overall, information technology seems that psychosocial interventions are more than efficacious when applied on patients who are at an early stage of the disease and who were euthymic when recruited [14, 95]. According to these post hoc analyses, a higher number of previous episodes [13, 40] as well as a higher psychiatric morbidity and more astringent functional harm [96] might reduce handling response, although the information are not conclusive [97]. As well, a differential effect has been proposed with neuroprotective strategies being better during the early on stages [98] and rehabilitative interventions being preferable at later stages [99].

Information technology is unclear whether IPSRT and CBT are efficacious during the acute episodes, merely there are some data in support [thirteen, 60, 78]. Maybe specific family unit environment characteristics might influence the response to treatment [70, 100]. Probably, there were subpopulations who especially benefited from these treatments [13, 70], but these assumptions are based on post hoc analyses alone.

It should be mentioned that well-nigh of the inquiry concerns pure and classic BD-I patients, although there are some rare information concerning special populations such equally BD-2 [36, 62], schizoaffective disorder [101, 102], patients with high suicide risk [85, 103, 104] and patients with comorbid substance corruption [105, 106].

It is interesting to note that the literature suggests that the benefits of psychosocial interventions if achieved could final for up to v years [36, 107], although some patients might need booster sessions [23, 108]. The complete range of the effect these interventions take is withal uncharted. Although it is reasonable to expect a beneficial consequence in a number of issues, including suicidality, enquiry data on these bug are virtually non-existent [103, 104].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the literature supports the notion that adjunctive specific psychological treatments can improve specific affliction outcomes. Although the data are rare, it seems reasonable that any such intervention should be practical as early as possible and should always exist tailored to the specific needs of the patient in the context of personalized patient care, since it is accepted that both the patients and their relatives have different needs and problems depending on the phase of the illness.

References

-

Fountoulakis KN, Kasper South, Andreassen O, Blier P, Okasha A, Severus E et al (2012) Efficacy of pharmacotherapy in bipolar disorder: a report past the WPA section on pharmacopsychiatry. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 262(Suppl 1):i–48

-

Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, Bowden C, Licht RW, Moller HJ et al (2013) The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2012 on the long-term handling of bipolar disorder. Globe J Biol Psychiatry 14(3):154–219

-

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi K, Flaxman AD, Michaud C et al (2012) Disability-adapted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Written report 2010. Lancet 380(9859):2197–2223

-

Rosa AR, Reinares M, Michalak EE, Bonnin CM, Sole B, Franco C et al (2010) Functional impairment and disability across mood states in bipolar disorder. Value Wellness xiii(8):984–988

-

Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM Jr, Baldessarini RJ, Strakowski SM, Stoll AL et al (2000) Two-yr syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of get-go-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry 157(2):220–228

-

Rosa AR, Reinares Grand, Amann B, Popovic D, Franco C, Comes K et al (2011) Six-calendar month functional outcome of a bipolar disorder cohort in the context of a specialized-intendance program. Bipolar Disord 13(7–8):679–686

-

Reinares M, Papachristou E, Harvey P, Mar BC, Sanchez-Moreno J, Torrent C et al (2013) Towards a clinical staging for bipolar disorder: defining patient subtypes based on functional outcome. J Affect Disord 144(1–2):65–71

-

Catala-Lopez F, Genova-Maleras R, Vieta East, Tabares-Seisdedos R (2013) The increasing burden of mental and neurological disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 23(xi):1337–1339

-

De DC, Ezquiaga E, Agud JL, Vieta East, Soler B, Garcia-Lopez A (2012) Subthreshold symptoms and fourth dimension to relapse/recurrence in a customs cohort of bipolar disorder outpatients. J Affect Disord 143(ane–iii):160–165

-

Berk L, Hallam KT, Colom F, Vieta E, Jerky M, Macneil C et al (2010) Enhancing medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. Hum Psychopharmacol 25(i):i–16

-

Fountoulakis G (2015) Bipolar disorder: an evidence-based guide to manic depression. Springer, New York

-

Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ (2013) Handling of bipolar disorder. Lancet 381(9878):1672–1682

-

Scott J, Paykel East, Morriss R, Bentall R, Kinderman P, Johnson T et al (2006) Cognitive-behavioural therapy for severe and recurrent bipolar disorders: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 188:313–320

-

Miller IW, Solomon DA, Ryan CE, Keitner GI (2004) Does adjunctive family therapy enhance recovery from bipolar I mood episodes? J Affect Disord 82(3):431–436

-

Meyer TD, Hautzinger M (2012) Cognitive behaviour therapy and supportive therapy for bipolar disorders: relapse rates for treatment period and two-year follow-upwardly. Psychol Med 42(7):1429–1439

-

de Barros PK, de O Costa 50, Silval KI, Dias VV, Roso MC, Bandeira Thou et al (2013) Efficacy of psychoeducation on symptomatic and functional recovery in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 127(ii):153–158

-

Gomes BC, Abreu LN, Brietzke E, Caetano SC, Kleinman A, Nery FG et al (2011) A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral group therapy for bipolar disorder. Psychother Psychosom lxxx(3):144–150

-

Reinares M, Sanchez-Moreno J, Fountoulakis KN (2014) Psychosocial interventions in bipolar disorder: what, for whom, and when. J Affect Disord 156:46–55

-

Fountoulakis KN, Siamouli K (2009) Re: how well do psychosocial interventions work in bipolar disorder? Tin J Psychiatry (Revue canadienne de psychiatrie) 54(8):578

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8(five):336–341

-

Lam DH, Watkins ER, Hayward P, Bright J, Wright K, Kerr Northward et al (2003) A randomized controlled study of cerebral therapy for relapse prevention for bipolar affective disorder: effect of the kickoff year. Arch Gen Psychiatry threescore(two):145–152

-

Lam DH, McCrone P, Wright M, Kerr N (2005) Price-effectiveness of relapse-prevention cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: 30-month study. Br J Psychiatry 186:500–506

-

Ball JR, Mitchell PB, Corry JC, Skillecorn A, Smith M, Malhi GS (2006) A randomized controlled trial of cerebral therapy for bipolar disorder: focus on long-term change. J Clin Psychiatry 67(2):277–286

-

Gonzalez IA, Echeburua Due east, Liminana JM, Gonzalez-Pinto A (2014) Psychoeducation and cerebral-behavioral therapy for patients with refractory bipolar disorder: a 5-year controlled clinical trial. Eur Psychiatry 29(iii):134–141

-

Zaretsky A, Lancee W, Miller C, Harris A, Parikh SV (2008) Is cognitive-behavioural therapy more effective than psychoeducation in bipolar disorder? Can J Psychiatry 53(7):441–448

-

Costa RT, Cheniaux East, Rosaes PA, Carvalho MR, Freire RC, Versiani Grand et al (2011) The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral group therapy in treating bipolar disorder: a randomized controlled report. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 33(2):144–149

-

Gonzalez Isasi A, Echeburua E, Liminana JM, Gonzalez-Pinto A (2014) Psychoeducation and cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with refractory bipolar disorder: a five-year controlled clinical trial. Eur Psychiatry 29(3):134–141

-

Fracalanza Chiliad, McCabe RE, Taylor VH, Antony MM (2014) The event of comorbid major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder on cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. J Affect Disord 162:61–66

-

Hollandare F, Eriksson A, Lovgren L, Humble MB, Boersma K (2015) Net-based cognitive behavioral therapy for residual symptoms in bipolar disorder type II: a single-subject design pilot written report. JMIR Res Protoc iv(two):e44

-

Jones SH, Smith One thousand, Mulligan LD, Lobban F, Law H, Dunn G et al (2015) Recovery-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy for recent-onset bipolar disorder: randomised controlled pilot trial. Br J Psychiatry 206(1):58–66

-

Steinan MK, Krane-Gartiser Thou, Langsrud K, Sand T, Kallestad H, Morken K (2014) Cognitive behavioral therapy for indisposition in euthymic bipolar disorder: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 15:24

-

Peet M, Harvey NS (1991) Lithium maintenance: 1. A standard education programme for patients. Br J Psychiatry 158:197–200

-

Harvey NS, Peet M (1991) Lithium maintenance: ii. Effects of personality and attitude on health information conquering and compliance. Br J Psychiatry 158:200–204

-

Dogan Due south, Sabanciogullari Southward (2003) The effects of patient education in lithium therapy on quality of life and compliance. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 17(half dozen):270–275

-

Perry A, Tarrier Due north, Morriss R, McCarthy E, Limb K (1999) Randomised controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to place early on symptoms of relapse and obtain treatment. BMJ 318(7177):149–153

-

Colom F, Vieta East, Sanchez-Moreno J, Palomino-Otiniano R, Reinares M, Goikolea JM et al (2009) Grouping psychoeducation for stabilised bipolar disorders: 5-twelvemonth event of a randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry 194(3):260–265

-

Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares K, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A et al (2003) A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose illness is in remission. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(4):402–407

-

Colom F, Vieta E, Reinares Yard, Martinez-Aran A, Torrent C, Goikolea JM et al (2003) Psychoeducation efficacy in bipolar disorders: beyond compliance enhancement. J Clin Psychiatry 64(nine):1101–1105

-

Lobban F, Taylor Fifty, Chandler C, Tyler Due east, Kinderman P, Kolamunnage-Dona R et al (2010) Enhanced relapse prevention for bipolar disorder past customs mental health teams: cluster feasibility randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry 196(1):59–63

-

Colom F, Reinares Thousand, Pacchiarotti I, Popovic D, Mazzarini L, Martinez AA et al (2010) Has number of previous episodes any effect on response to group psychoeducation in bipolar patients? Acta Neuropsychiatrica 22:l–53

-

Javadpour A, Hedayati A, Dehbozorgi GR, Azizi A (2013) The impact of a simple individual psycho-education program on quality of life, rate of relapse and medication adherence in bipolar disorder patients. Asian J Psychiatry 6(iii):208–213

-

Kurdal Eastward, Tanriverdi D, Savas HA (2014) The result of psychoeducation on the functioning level of patients with bipolar disorder. West J Nurs Res 36(3):312–328

-

Scott J, Colom F, Popova E, Benabarre A, Cruz Due north, Valenti Chiliad et al (2009) Long-term mental health resource utilization and cost of care following grouping psychoeducation or unstructured group back up for bipolar disorders: a price–do good analysis. J Clin Psychiatry lxx(3):378–386

-

Parikh SV, Zaretsky A, Beaulieu S, Yatham LN, Young LT, Patelis-Siotis I et al (2012) A randomized controlled trial of psychoeducation or cerebral-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a Canadian Network for Mood and Feet treatments (CANMAT) study [CME]. J Clin Psychiatry 73(half dozen):803–810

-

Smith DJ, Griffiths E, Poole R, di Florio A, Barnes E, Kelly MJ et al (2011) Beating bipolar: exploratory trial of a novel Internet-based psychoeducational treatment for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 13(5–6):571–577

-

Proudfoot J, Parker 1000, Manicavasagar V, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Whitton A, Nicholas J et al (2012) Effects of adjunctive peer support on perceptions of illness command and agreement in an online psychoeducation program for bipolar disorder: a randomised controlled trial. J Touch on Disord 142(1–iii):98–105

-

Castle D, White C, Chamberlain J, Berk M, Berk 50, Lauder S et al (2010) Group-based psychosocial intervention for bipolar disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 196(v):383–388

-

van der Voort TY, van Meijel B, Goossens PJ, Hoogendoorn AW, Draisma Southward, Beekman A et al (2015) Collaborative intendance for patients with bipolar disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 206(5):393–400

-

Fiorillo A, Del Vecchio V, Luciano One thousand, Sampogna G, De Rosa C, Malangone C et al (2014) Efficacy of psychoeducational family unit intervention for bipolar I disorder: a controlled, multicentric, existent-world study. J Affect Disord 172C:291–299

-

Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, Glick H, Kinosian B, Altshuler L et al (2006) Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part Ii. Touch on on clinical issue, function, and costs. Psychiatr Serv 57(7):937–945

-

Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Bauer MS, Unutzer J, Operskalski B (2006) Long-term effectiveness and toll of a systematic intendance program for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63(five):500–508

-

Eker F, Harkin S (2012) Effectiveness of half-dozen-week psychoeducation plan on adherence of patients with bipolar melancholia disorder. J Affect Disord 138(3):409–416

-

Faria Advertising, de Mattos Souza LD, de Azevedo Cardoso T, Pinheiro KA, Pinheiro RT, da Silva RA et al (2014) The influence of psychoeducation on regulating biological rhythm in a sample of patients with bipolar II disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Psychol Res Behav Manag 7:167–174

-

de Cardoso TA, de Farias CA, Mondin TC, da Silva GDG, Souza LD, da Silva RA et al (2014) Brief psychoeducation for bipolar disorder: impact on quality of life in immature adults in a 6-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res 220(3):896–902

-

Cuhadar D, Cam MO (2014) Effectiveness of psychoeducation in reducing internalized stigmatization in patients with bipolar disorder. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 28(1):62–66

-

Todd NJ, Jones SH, Hart A, Lobban FA (2014) A spider web-based self-management intervention for bipolar disorder 'living with bipolar': a feasibility randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord 169:21–29

-

Barnes CW, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Wilhelm K, Mitchell Pb (2015) A web-based preventive intervention program for bipolar disorder: outcome of a 12-months randomized controlled trial. J Touch Disord 174:485–492

-

Depp CA, Ceglowski J, Wang VC, Yaghouti F, Mausbach BT, Thompson WK et al (2015) Augmenting psychoeducation with a mobile intervention for bipolar disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord 174:23–30

-

Bond Thousand, Anderson IM (2015) Psychoeducation for relapse prevention in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of efficacy in randomized controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 17(4):349–362

-

Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Thase ME, Mallinger AG, Swartz HA, Fagiolini AM et al (2005) Two-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(nine):996–1004

-

Frank E, Soreca I, Swartz HA, Fagiolini AM, Mallinger AG, Thase ME et al (2008) The function of interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in improving occupational performance in patients with bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry 165(12):1559–1565

-

Swartz HA, Frank E, Cheng Y (2012) A randomized pilot written report of psychotherapy and quetiapine for the acute treatment of bipolar II depression. Bipolar Disord 14(two):211–216

-

Inder ML, Crowe MT, Luty SE, Carter JD, Moor Southward, Frampton CM et al (2015) Randomized, controlled trial of Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy for immature people with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 17(2):128–138

-

van Gent EM, Zwart FM (1991) Psychoeducation of partners of bipolar-manic patients. J Affect Disord 21(1):15–eighteen

-

Miklowitz DJ, Simoneau TL, George EL, Richards JA, Kalbag A, Sachs-Ericsson N et al (2000) Family-focused handling of bipolar disorder: i-year effects of a psychoeducational program in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. Biol Psychiatry 48(half-dozen):582–592

-

Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Richards JA, Simoneau TL, Suddath RL (2003) A randomized written report of family unit-focused psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disorder. Curvation Gen Psychiatry 60(nine):904–912

-

Rea MM, Tompson MC, Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ, Hwang Due south, Mintz J (2003) Family-focused treatment versus individual handling for bipolar disorder: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 71(3):482–492

-

Scott J, Colom F, Pope Grand, Reinares M, Vieta Due east (2012) The prognostic role of perceived criticism, medication adherence and family knowledge in bipolar disorders. J Touch on Disord 142(one–three):72–76

-

Clarkin JF, Carpenter D, Hull J, Wilner P, Glick I (1998) Effects of psychoeducational intervention for married patients with bipolar disorder and their spouses. Psychiatr Serv 49(four):531–533

-

Miller IW, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Uebelacker LA, Johnson SL, Solomon DA (2008) Family unit treatment for bipolar disorder: family impairment by treatment interactions. J Clin Psychiatry 69(5):732–740

-

Solomon DA, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Kelley J, Miller IW (2008) Preventing recurrence of bipolar I mood episodes and hospitalizations: family psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy versus pharmacotherapy alone. Bipolar Disord 10(vii):798–805

-

Reinares Grand, Colom F, Sanchez-Moreno J, Torrent C, Martinez-Aran A, Comes K et al (2008) Impact of caregiver grouping psychoeducation on the form and outcome of bipolar patients in remission: a randomized controlled trial. Bipolar Disord x(4):511–519

-

Reinares M, Vieta E, Colom F, Martinez-Aran A, Torrent C, Comes M et al (2004) Impact of a psychoeducational family intervention on caregivers of stabilized bipolar patients. Psychother Psychosom 73(5):312–319

-

Madigan K, Egan P, Brennan D, Loma Due south, Maguire B, Horgan F et al (2012) A randomised controlled trial of carer-focussed multi-family grouping psychoeducation in bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry 27(iv):281–284

-

Perlick DA, Miklowitz DJ, Lopez N, Chou J, Kalvin C, Adzhiashvili V et al (2010) Family unit-focused treatment for caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 12(6):627–637

-

D'Souza R, Piskulic D, Sundram Southward (2010) A brief dyadic group based psychoeducation program improves relapse rates in recently remitted bipolar disorder: a airplane pilot randomised controlled trial. J Bear upon Disord 120(one–3):272–276

-

Fredman SJ, Baucom DH, Boeding SE, Miklowitz DJ (2015) Relatives' emotional involvement moderates the effects of family therapy for bipolar disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 83(1):81–91

-

Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Wisniewski SR, Kogan JN et al (2007) Psychosocial treatments for bipolar depression: a 1-yr randomized trial from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64(4):419–426

-

Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Kogan JN, Sachs GS et al (2007) Intensive psychosocial intervention enhances performance in patients with bipolar depression: results from a 9-month randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 164(nine):1340–1347

-

Deckersbach T, Nierenberg AA, Kessler R, Lund HG, Ametrano RM, Sachs Grand et al (2010) Inquiry: cerebral rehabilitation for bipolar disorder: an open trial for employed patients with residuum depressive symptoms. CNS Neurosci Ther 16(v):298–307

-

Martinez-Aran A, Torrent C, Sole B, Bonnin CM, Rosa AR, Sanchez-Moreno J et al (2011) Functional remediation for bipolar disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Wellness vii:112–116

-

Torrent C, Bonnin CM, Martinez-Aran A, Valle J, Amann BL, Gonzalez-Pinto A et al (2013) Efficacy of functional remediation in bipolar disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled written report. Am J Psychiatry 170(8):852–859

-

Lahera G, Benito A, Montes JM, Fernandez-Liria A, Olbert CM, Penn DL (2013) Social cognition and interaction preparation (SCIT) for outpatients with bipolar disorder. J Touch on Disord 146(1):132–136

-

Sole B, Bonnin CM, Mayoral One thousand, Amann BL, Torres I, Gonzalez-Pinto A et al (2015) Functional remediation for patients with bipolar 2 disorder: improvement of functioning and subsyndromal symptoms. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25(2):257–264

-

Williams JM, Alatiq Y, Crane C, Barnhofer T, Fennell MJ, Duggan DS et al (2008) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in bipolar disorder: preliminary evaluation of immediate effects on between-episode operation. J Affect Disord 107(1–3):275–279

-

Ives-Deliperi VL, Howells F, Stein DJ, Meintjes EM, Horn Due north (2013) The effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in patients with bipolar disorder: a controlled functional MRI investigation. J Affect Disord 150(3):1152–1157

-

Perich T, Manicavasagar V, Mitchell Lead, Ball JR, Hadzi-Pavlovic D (2013) A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 127(v):333–343

-

Perich T, Manicavasagar V, Mitchell Lead, Ball JR (2013) The association between meditation practice and treatment upshot in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder. Behav Res Ther 51(7):338–343

-

Howells FM, Ives-Deliperi VL, Horn NR, Stein DJ (2012) Mindfulness based cognitive therapy improves frontal control in bipolar disorder: a pilot EEG study. BMC Psychiatry 12:15

-

Stange JP, Eisner LR, Holzel BK, Peckham AD, Dougherty DD, Rauch SL et al (2011) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: furnishings on cognitive functioning. J Psychiatr Pract 17(6):410–419

-

Van DS, Jeffrey J, Katz MR (2013) A randomized, controlled, pilot study of dialectical behavior therapy skills in a psychoeducational grouping for individuals with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 145(3):386–393

-

Bos EH, Merea R, van den Brink E, Sanderman R, Bartels-Velthuis AA (2014) Mindfulness training in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample: outcome evaluation and comparison of different diagnostic groups. J Clin Psychol 70(i):threescore–71

-

Colom F, Vieta Eastward, Sanchez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Goikolea JM et al (2005) Stabilizing the stabilizer: group psychoeducation enhances the stability of serum lithium levels. Bipolar Disord vii(Suppl 5):32–36

-

Simoneau B, Lavallee P, Anderson PC, Bailey M, Bantle 1000, Berthiaume S et al (1999) Discovery of non-peptidic P2-P3 butanediamide renin inhibitors with high oral efficacy. Bioorg Med Chem 7(iii):489–508

-

Scott J, Colom F, Vieta E (2007) A meta-analysis of relapse rates with adjunctive psychological therapies compared to usual psychiatric handling for bipolar disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 10(1):123–129

-

Reinares M, Colom F, Rosa AR, Bonnin CM, Franco C, Sole B et al (2010) The impact of staging bipolar disorder on treatment outcome of family psychoeducation. J Affect Disord 123(1–three):81–86

-

Lam DH, Burbeck R, Wright M, Pilling South (2009) Psychological therapies in bipolar disorder: the effect of disease history on relapse prevention—a systematic review. Bipolar Disord 11(5):474–482

-

Kapczinski F, Dias VV, Kauer-Sant'Anna M, Frey BN, Grassi-Oliveira R, Colom F et al (2009) Clinical implications of a staging model for bipolar disorders. Expert Rev Neurother 9(vii):957–966

-

Berk M, Conus P, Lucas N, Hallam 1000, Malhi GS, Dodd S et al (2007) Setting the phase: from prodrome to treatment resistance in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 9(7):671–678

-

Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, George EL, Taylor DO, Schneck CD, Sullivan AE et al (2009) Expressed emotion moderates the furnishings of family-focused handling for bipolar adolescents. J Am Acad Kid Adolesc Psychiatry 48(6):643–651

-

Vieta E (2010) Individualizing treatment for patients with schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 71(ten):e26

-

Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, Nivoli AM, Colom F, Vieta E (2012) Is schizoaffective disorder still a neglected condition in the scientific literature? Psychother Psychosom 81(6):389–390

-

Fountoulakis KN, Gonda Ten, Siamouli G, Rihmer Z (2009) Psychotherapeutic intervention and suicide run a risk reduction in bipolar disorder: a review of the testify. J Bear upon Disord 113(1–2):21–29

-

Fountoulakis KN, Siamouli M (2009) Re: how well practise psychosocial interventions work in bipolar disorder? Can J Psychiatry 54(8):578

-

Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Kolodziej ME, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, Daley DC et al (2007) A randomized trial of integrated group therapy versus group drug counseling for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence. Am J Psychiatry 164(1):100–107

-

Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Jaffee WB, Bender RE, Graff FS, Gallop RJ et al (2009) A "community-friendly" version of integrated group therapy for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 104(3):212–219

-

Gonzalez-Isasi A, Echeburua E, Mosquera F, Ibanez B, Aizpuru F, Gonzalez-Pinto A (2010) Long-term efficacy of a psychological intervention program for patients with refractory bipolar disorder: a airplane pilot study. Psychiatry Res 176(2–iii):161–165

-

Lam D, Donaldson C, Brown Y, Malliaris Y (2005) Brunt and marital and sexual satisfaction in the partners of bipolar patients. Bipolar Disord 7(v):431–440

Authors' contributions

KNF SM, SM and ET carried out the literature search and the estimation of the results. KNF wrote the showtime draft and all the other authors contributed to the revision including the final draft. All authors read and approved the terminal manuscript.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miziou, South., Tsitsipa, E., Moysidou, S. et al. Psychosocial handling and interventions for bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Ann Gen Psychiatry 14, nineteen (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-015-0057-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-015-0057-z

Keywords

- Bipolar Disorder

- Bipolar Disorder Patient

- Mood Episode

- Cognitive Remediation

- Group Psychoeducation

Source: https://annals-general-psychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12991-015-0057-z

0 Response to "A Review of Evidence-based Psychosocial Interventions for Bipolar Dis- Order"

Post a Comment